VENEZUELA COMMEMORATED THE EIGHTH YEAR ANNIVERSARY OF THE COUP D’ETAT BACKED BY WASHINGTON THAT CHANGED THE BOLIVARIAN REVOLUTION FOREVER

In just 47 hours, a coup d’etat ousted President Chavez and a countercoup returned him to power, in an extraordinary showing of the will and determination of a dignified people on a revolutionary path with no return. The mass media played a major role in advancing the coup and spreading false information internationally in order to justify the coup plotters’ actions. CIA documents revealed US government involvement and support to the coup organizers

When Hugo Chavez was elected President in 1998, the Clinton administration maintained a « wait and see » policy. Venezuela had been a faithful servant to US interests throughout the twentieth century, and despite the rhetoric of revolution spoken by President Chavez, few in Washington believed changed was imminent.

But after Chavez followed through on his first and principal campaign promise, to initiate a Constitutional Assembly and redraft the nation’s magna carta, everything began to change.

The new Constitution was written and ratified by the people of Venezuela, in an extraordinary demonstration of participatory democracy. Throughout the nation in early 1999, all Venezuelans were invited to aid in the creation of what would become one of the most advanced constitutions in the world in the area of human rights. The draft text of 350 articles, which included a chapter dedicated to indigenous peoples’ rights, along with the rights to housing, healthcare, education, nutrition, work, fair wages, equality, recreation, culture, and a redistribution of the oil industry production and profit, was ratified by national referendum towards the end of 1999 by more than 70% of voters.

Elections were immediately convened under the new constitutional structure, and Chavez won again with an even larger majority, around 56%. Once in office in 2000, laws were implemented to guarantee the new rights accorded in the Constitution, and interests were affected. Venezuela assumed the presidency of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), with oil at approximately $7 USD a barrel. Quickly, under Venezuela’s leadership, which sought to benefit oil producing nations and not those supplied, oil rose to more than $25 USD a barrel. Washington was uneasy with these changes, but still was « waiting to see » how far the changes would go.

CHANGES WASHINGTON DISAPPROVED

In 2001, the Bolivarian Revolution proposed by President Chavez began to take form. The oil industry was in the process of being restructured, hydrocarbons laws were passed that would allow for a redistribution of oil profits and Chavez was recuperating an industry - nationalized in 1976 - that was on the path to privatization. An opposition began to grow internally in Venezuela, primarily composed of the economic and political elite that ruled the country throughout the prior 40 years, now unhappy with the real changes taking effect. Aligned with those interests were the owners of Venezuela’s media outlets - television, radio and print, which belonged to the old oligarchy in the country.

In early 2001, President Chavez attended the Summit of the Americas meeting in Quebec, Canada. By now, Washington had undergone its own changes and George W. Bush had moved into the White House. President Bush also was present at the meeting in Quebec, and there announced the US plan to expand free trade throughout the Americas - the Free Trade of the Americas Act (FTAA). Hugo Chavez was the only head of state at the summit to oppose Washington’s plan. It was the first showing of his « insubordination » to US agenda.

Later that year, after the devastating and tragic attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City, Washington began a bombing campaign in Afghanistan. President Chavez publicly declared the bombing of Afghanistan and the killing of innocent women and children as an act of terror. « This is fighting terror with more terror » he declared on national television in October 2001. The declaration produced Washington’s first official response.

US Ambassador to Caracas at the time, Donna Hrinak, paid a visit to Chavez in the presidential palace shortly after. During her encounter with the Venezuelan President, she proceeded to read a letter from Washington, demanding Chavez publicly retract his statement about Afghanistan. The Venezuelan head of state declined the request and informed the US Ambassador that Venezuela was now a sovereign state, no longer subordinate to US power.

Hrinak was recalled to Washington and a new ambassador was sent to Venezuela, an expert in coup d’etats.

WASHINGTON ORGANIZES THE COUP

As Washington’s concern grew over the changes taken place in Venezuela, and the insubordination of the Venezuelan President, business groups and powerful interests inside Venezuela began to contemplate Chavez’s removal. Those running the state-owned oil company, PDVSA, were adament to defend their positions and control over the company, as well as their mass profits, which instead of being invested in the country were being coveted in the oil executives’ pockets.

A US entity, created by US Congress in 1983 and overseen by the State Department, the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), began to channel hundreds of thousands of dollars to groups inside Venezuela to help consolidate the opposition movement and make plans for the coup. School of the Americas-trained Venezuelan military officers began to coordinate with their US counterparts to organize Chavez’s ouster. And the US Embassy in Caracas, with the recently arrived Ambassador Charles Shapiro, was helping to put the final touches on the coup d’etat.

« The right man for the right time » in Venezuela, said an Embassy cable sent to Washington in December 2001, referring to Pedro Carmona, the head of Venezuela’s Chamber of Commerce, Fedecamaras. Carmona was signaled out as the « president-to-be » after the coup succeeded. That December 2001, oil industry executives led a strike, and called for Chavez’s resignation. Their furor began to grow in early 2002 and by March, the strikes and protests against President Chavez were almost a daily occurrence.

The NED quadrupled its funding to Venezuelan groups, such as Fedecamaras and the CTV labor federation, along with a series of NGOs plotting Chavez’s ouster. A State Department cable from the first week of March 2002 claimed « Another piece falls in to place » and applauded the opposition’s efforts to finally create a plan for a transitional government : « With much fanfare, the Venezuelan great and good assembled on March 5 in Caracas’ Esmeralda Auditorium to hear representatives of the Confederation of Venezuelan Workers (CTV), the Federation of Business Chambers (Fedecamaras) and the Catholic Church present their ‘Bases for a Democratic Accord’, ten principles on which to guide a transitional goverment ».

Soon after, a March 11, 2002 Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) top secret brief, partially desclassifed by Jeremy Bigwood and Eva Golinger through investigations using the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), revealed a coup plot underway in Venezuela. « The opposition has yet to organize itself into a united front. If the situation further deteriorates and demonstrations become even more violent…the military may move to overthrow him ».

Yet another CIA top secret brief from April 6, 2002, just five days before the coup, outlined the detailed plans of how the events would unravell, « Conditions Ripening for Coup Attempt…Dissident military factions, including some disgruntled senior officers and a group of radical junior officers, are stepping up efforts to organize a coup against President Chavez, possibly as early as this month…The level of detail in the reported plans…targets Chavez and 10 other senior officials for arrest…To provoke military action, the plotters may try to exploit unrest stemming from opposition demonstrations slated for later this month… ».

A CORPORATE-MEDIA-MILITARY AFFAIR

National papers in Venezuela headlined on April 10-11, 2002 that the « Final battle will be in Miraflores », the Venezuelan presidential palace, hinting that the media knew the coup was undeway. That April 11, a rally began at the PDVSA headquarters in Eastern Caracas. The rally turned into a march of several hundred thousand people protesting against President Chavez and calling violently for his ouster. Those leading the rally, the presidents of the CTV, Fedecamaras and several high level military officers who had already declared rebellion just a day before, directed the marchers towards the presidential palace, despite not having authorization for the route.

Meanwhile, outside the presidential palace, Chavez supporters had gathered to support their President and protect the area from the violent opposition marchers on the way. But before the opposition march even reached the palace or the area near the pro-Chavez rally, shots were fired and blood began to spill in both the pro- and anti-Chavez demonstrations. Snipers had been placed strategically on the buildings in downtown Caracas and had open fired on the people below.

Pro-Chavez supporters on the bridge right next to the palace, Puente Llaguno, fired back at the snipers, and the metropolitan police forces, who were firing at them. A Venevision camera crew, positioned near the pro-Chavez rally, took images of the firefight and quickly returned to the studio to edit the material and produce a breaking news story showing the pro-Chavez supporters firing guns with a voice-over stating they were firing on « peaceful opposition protestors ». The images were rapidly reproduced and repeated over and over again on Venezuelan national television to justify calls for Chavez’s removal. The manipulated images were later shown around the world and used to blame President Chavez for the dozens of deaths that occured that April 11, 2002. The truth didn’t come out until after the dust had settled and the coup was defeated. The television crew had been told to take the footage and manipulate it, under direct orders from Gustavo Cisneros, owner of Venevision and a variety of other media conglomerates and companies, and also the wealthiest man in Venezuela.

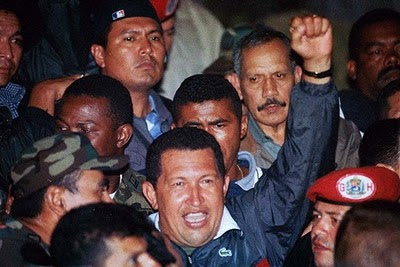

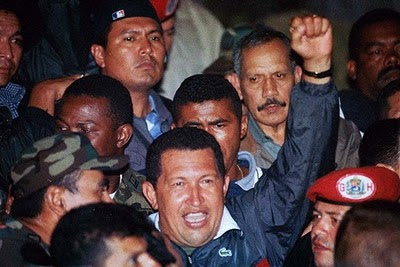

The high military command turned on President Chavez and took him into custody. He was taken to a military base on an island off Venezuela’s coast, where he was either to be assassinated or sent to Cuba. Meanwhile, the « right man for the right time » in Venezuela, Pedro Carmona - designated by Washington, swore himself in as President on April 12, 2002, and proceeded to read a decree dissolving all of Venezuela’s democratic institutions.

COUNTER-COUP AND REVOLUTION

As the Venezuelan people awoke to television networks claiming « Good morning Venezuela, we have a new president » and applauding the violent coup that had occured a day ealier, resistance began to grow. Once the « Carmona Decree » was issued, Venezuelans saw their worst fears coming true - a return to the repressive governments of the past that excluded and mistreated the majority of people in the country. And Chavez was absent, no one knew where he was.

Between April 12-13, Venezuelans began pouring into the streets of Caracas, demanding a return of President Chavez and an ouster of the coup leaders. Meanwhile, the Bush administration had already issued a statement recognizing the coup government and calling on other nations to do the same.

But the coup resistance grew to millions of people, flooding the areas surrounding the presidential palace, and the presidential guard, still loyal to Chavez, moved to retake the palace. Word of the resistance reached military barracks throughout the country, and one in Maracay, outside of Caracas, acted quickly to locate and rescue Chavez and return him to the presidential palace.

By the early morning hours of April 14, Chavez had returned, brought back by the will and power of the Venezuelan people and the loyal armed forces.

These events changed Venezuela forever and awoke the consciousness of many who had underestimated the importance and vulnerability of their Revolution.